Vivere Project in AI (in Minecraft)

Summary of the Project

Our project is similar to that of an “escape room,” where the agent must find an exit of a room within a reasonable amount of time. However, the agent must avoid death as there is a fire that spreads throughout the map. As a result, dying is equivalent to a penalty and finding exits with a with minimal number of steps is equivalent to rewards.

Approach

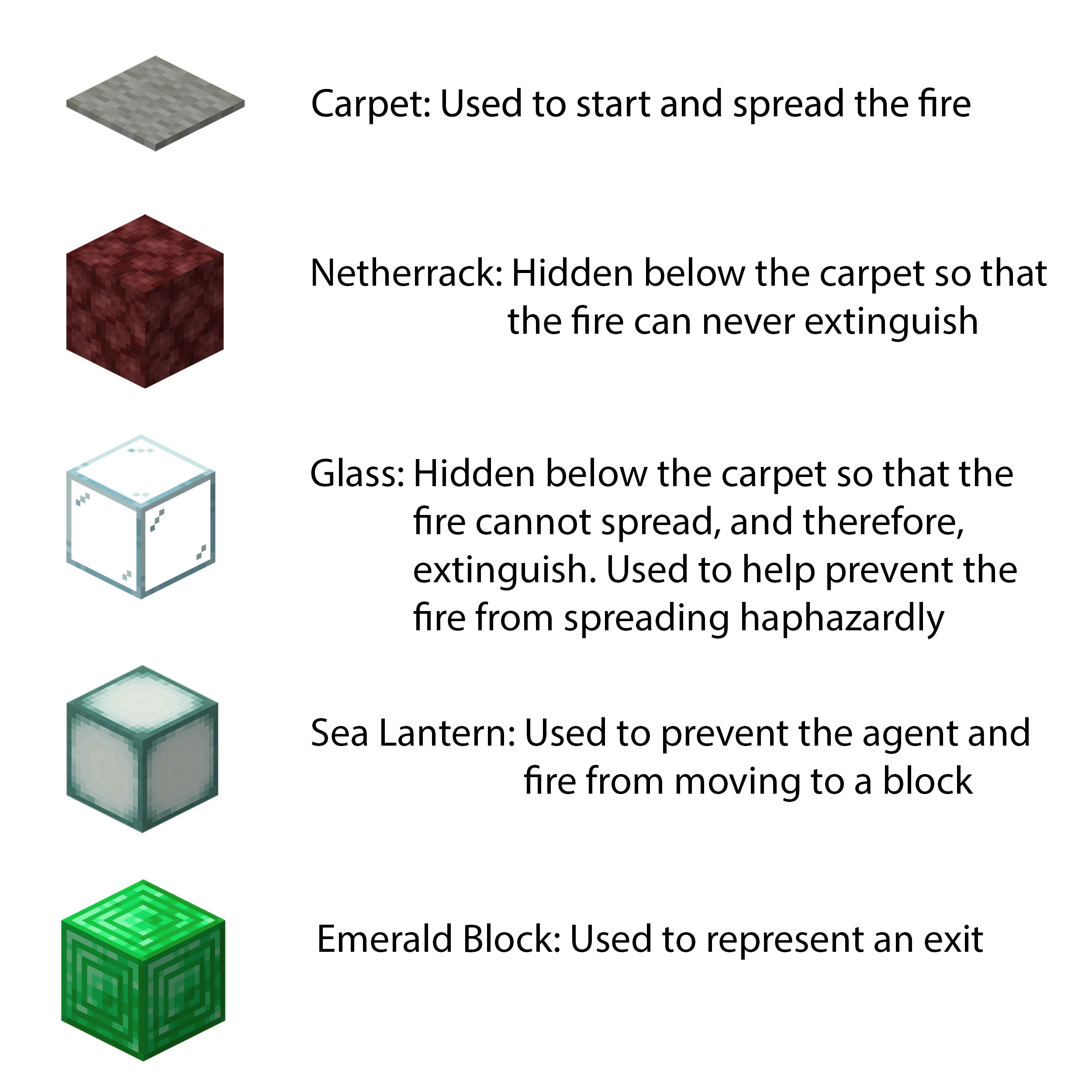

To start this project, we first created random maps by writing a program that helps us generate a map via XML strings. The user will input the size of the map he or she wants, and shortly after, the program will output a long string for the map. This map includes exit point(s), blocks/areas where the agent is not able to access, and a location for the fire to start spreading. It is important to note the material of the generated map. We decided to set the material of the floor to be carpet so that the fire can spread; however, in Minecraft, it is normal for the fire to go out after a certain period of time. To battle this, we put netherrack blocks below the carpet so that when the carpet burns out, the fire continues and never extinguishes. In order to have our fire spread in a somewhat ‘controlled path’ so that it does not spread everywhere, we used glass instead of netherrack. Next, in order to block the agent and fire from a certain path or block, we used sea lanterns. Lastly, we used emerald blocks to mark an exit. The following images displays each block type and its purpose in our map.

Randomized Maps

To avoid overfitting our agent on one kind of map, we applied the randomized Prim’s algorithm to write our own randomized map generator to get large numbers of maps to train and test our agent. The following shows a modified version of randomized Prim’s algorithm:

- Build a 2D grid of blocks;

- Randomly pick a cell in the grid, mark it as a part of the passage. This is our starting cell;

- Compute frontier cells of current cell. A frontier cell is a cell which is 2 blocks away from current cell and is not a part of the passage and within the grid;

- While frontier cells set is not empty:

- Randomly select a frontier cell from frontier cells set, mark it as a part of passage;

- Compute neighbor cells of current frontier cell. A neighbor cell is a cell which is 2 blocks away from current frontier cell and is NOT a part of passage and within the grid.

- Randomly select a neighbor cell from the neighbor cells set;

- Connect this neighbor cell and the frontier cell by marking this neighbor cell and the cell in-between as a part of passage;

- Compute new frontier cells and add them into frontier cells set;

- Remove current frontier cell from frontier cells set.

The image below shows an example of a randomly generated 5x5- and 7x7- size maze respectfully.

In our original idea, our agent should dodge burning blocks to reach the exits. However, not every randomized maze with spreading fire can suffice our needs of training. For example, certain randomly generated mazees have only 1-2 ‘safe areas’ the agent can move - which makes that specific maze nearly impossible to solve. The difficulty of a maze and spreading speed of the fire both have huge influences on the agent’s performance. Therefore, the design of our maze is constantly evolving during the training. Based on the feedback from the agent while monitoring the training progress, we gradually adjusted our mazes by:

- Randomly alternate flammable (carpet) and inflammable (glass) blocks to build the passage of the maze to restrain the fire from spreading too fast.

- Use multiple exits and clear the surrrounding of the exits to simplify the path to the goal

- Coarsely browse randomly generated mazes and delete ‘difficult’ ones, such as mazes having only one or two empty spaces to walk through in a row or a column, to speed up training efficiency.

By all the three methods above, the agent has significantly improved its chance of surviving, which allows it to have enough time to collect information and actually “learn” from every maze it tried. Malmo also allows the user to get the world state object from the agent host. From the world state, we can get observations such as the grid representation of the maze. With that, we can modify the speed at which our agent makes a move.

In addition, video frames in Minecraft and Malmo contain information of the world state. As such, whenever there is a change in Minecraft, a new video frame, that has the new information of the current world state, is created, and Malmo keeps track of how many video frames have passed since the previous state of the world. With this information, we modified our agent to make moves but to also save the resulting new state for every 3 video frames of the game. With these attributes, we trained our agent.

Our training sessions are listed below:

Step 1: 5x5-sized grids, no maze (eg obstacles), no fire, and one exit. Agent is spawned in a fixed position on one side.

- Result: Agent can find the exit properly. Algorithm is functional.

Step 2: 5x5-sized grids, trained 1000 episodes. Now with randomly selected mazes from 5 mazes in every 10 episodes. All the blocks are flammable and fires will not fade away. One fire is spawned in a fixed position. Agent is spawned in a fixed position on one side. There are three exits on the other 3 sides of the map.

- Result: Overfitting. The agent learns to go only straight, relative to its current position. It also cannot avoid fire since it spreads too fast, and after a short time, there is no place for it to hide or dodge the fire.

- Solution: Expand the grid while increasing the maze set. Expanding the grid will give the agent more room to dodge or hide from the fire, and increasing the maze set will introduce more diverse maps to decrease overfitting.

Step 3: 7x7-sized grid, trained 1000 episodes. Randomly selecting a maze from 50 mazes in every 10 episodes. There is a 50% chance for a passage to be flammable which significantly decreases the fire’s influence, so we spawned 2 fixed fires. Agent is spawned in a fixed position on one side. There are three exits on the other 3 sides of the map.

- Result: Overfitting is still present. Agent still learns to go straight only, relative to its position, but the survival rate has improved since it learns to escape from the fires.

- Solution: Increase the maze set more to combat the overfitting agent.

Step 4: 7x7-sized grid, trained 1000 episodes. Randomly selecting a maze from 160 mazes in every 5 episodes. Any other conditions remain the same.

- Result: Still, the agent continues to reach one exit, namely the bottom exit. We assume that the agent tries to avoid fire on the left side which prevents it from reaching the left exit. The bottom exit is closer than the right exit, so the agent continues to go straight to the bottom one.

- Solution: Keep two exits only in the maze by randomly removing the left exit or the bottom exit in order to have our agent learn to move towards different exits. We hope this can encourage the agent to go the right exit. In addition, we increase the randomness of the mazes.

Step 5: 7x7-sized grid, trained 2000 episodes. Randomly selecting a maze from 1000 mazes in every 3 episodes. One right exit, and one left or bottom exit. Every other conditions is the same.

- Result: The agent gets much smarter now. It solves 5 easy or medium testing maps using 30 steps on average which is a huge improvement.

Further Exploration:

We continue to train the model from step 5 in 7x7 mazes, but instead of using one video frame, we changed our algorithm to use three video frames. After 4000 episodes, the result was not optimal. Consequently, our following Evaluation section focuses on the 7x7 grid, trained on 2000 episodes.

We also decided to include a larger map (10x10) with the model trained from step 5:

A 10x10-sized grid, trained for ~1600 episodes. Randomly selecting a maze from 1000 mazes in every 3 episodes. Other conditions are kept the same as the 7x7 grid conditions.

- Result: The agent can not find an exit anymore, since the maze is getting much larger than before. We anticipated this and already selected simple mazes for training. However, most of the time, the agent cannot find the exit within a 1.5 minute time limit at each episode. (We also tried to set the time limit to 15 minutes, but the result was not optimal.) Considering the time required for training in total, we stopped after 1600 episodes and decided to focus on perfecting the 7x7-grids.

Deep-Q Learning

For the artificial intelligence, we decided to use the Deep-Q Learning algorithm which uses greedy-epsilon based policy. Deep-Q Learning is based on the following:

We used this formula in our algorithm and defined the variables as followed:

- S: the current state which is the grid observation (eg a birds eye view of the map). It includes the information of our maze and the surroundings relative to the agent. Alternatively, the agent is able to see its surroundings as a grid, where the agent is at the center.

- S’: Next state after taking action A’

- A: the current action that our agent will take. Currently, our agent can make four moves [move north, move south, move east, move west].

- A’: the future action

- R: is our expected reward based on the action our agent takes.

- γ (gamma): Discount factor. We set our gamma = 0.99 as that is the staple norm in Q-learning.

We used Tensorflow to build our Neural Network, and our network consists of three convolutional layers, followed by 2 fully connected layers. The last fully connected layer outputs values from 0-3 which is mapped to our action space. As for our input to the network, we used a little trick: Malmo offers a feature to observe the surrounding blocks by

The techniques we used for our Deep Q-Network (DQN) is the Experience Replay Memory and uses two separate networks: Q-network and Target Network.

-

The Replay Memory consists of tuples of [ “state”, “action”, “reward”, “next_state”, “done”]. We then use the Replay Memory to sample a batch of size 32 to train our agent. Each step an agent takes is stored in the replay memory. In the beginning of training, we fill around 10% of the total replay memory with random exploration and gradually fill it as the agent trains. Once it is filled, the earliest memory is popped.

-

The Target Network is used for calculating our loss and updates every N number of episodes. For our loss value, we use the squared differences of the Q-network and Target Network and performed gradient descent on it.

To evaluate our progress, we used one of Tensorflow features, Tensorboard, to display the metrics. With the help of Tensorflow and Tensorboard in our approach, we were able to obtain a graphical model of our data and its trends to ensure that our agent is working properly such that it fulfills our sanity case - that our agent does not constantly die in the fire.

It is important to note the random maze generation in use with Tensorflow and Tensorboard, since the maze generator gave us insight about the current input and environment the agent is being trained. To review, the random maze generator allows the user to choose his or her maze size and generate an XML file. In order to avoid our agent from overfitting to only one map, we incorporated multiple random mazes into our training process. Every 20 episodes, we randomly choose from one of our randomly generated mazes and train the agent on that map. Even during Experience Replay Memory initialization, with every 20 steps, we change the maze. Doing this increases our training time and makes it harder for the agent to learn but prevents the agent from overfitting to one specific map and help our agent to perform well on unseen test map.

Evaluation

As an overview, we decided on the following factors for our analysis:

Baseline:

Our baseline is so that the agent does not die in the fire and is able to find the exit. We still hold true to this baseline, but in addition, we also included our status report’s baseline: a random agent that can perform random movements until it either dies to the spreading fire or exits the maze by luck.

Quantitative Analysis:

The number of steps taken to find the exit. Ideally, we would want the number of steps to have a general decreasing trend on a graph. During the training process, we should see an increase in the reward. It indicates that agent is solving the maze quicker each time, since there is a penalty for each extra move the agent makes.

Qualitative Analysis:

The agent does not run into the fire and die; alternatively, the agent is able to escape the fire, should it run into it.

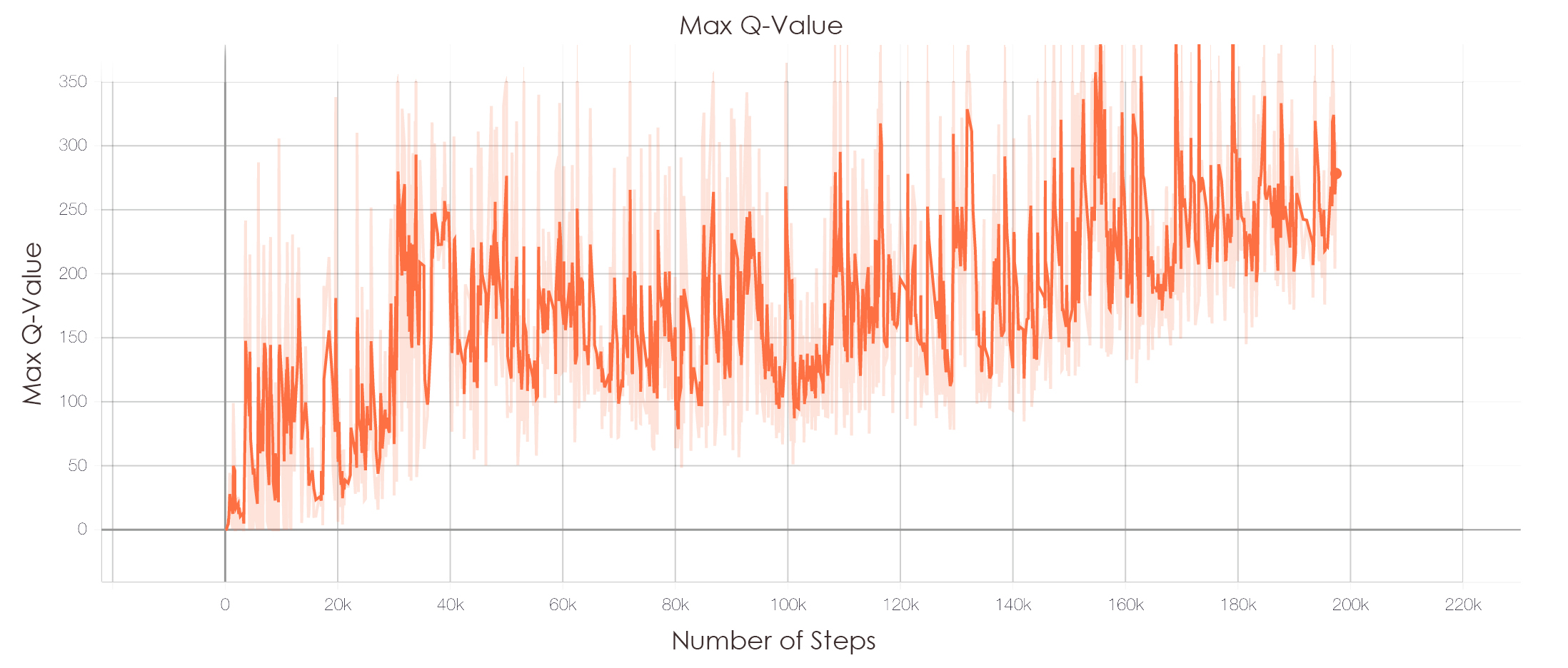

The following graphs represent our current progress on the algorithm and agent’s performance.

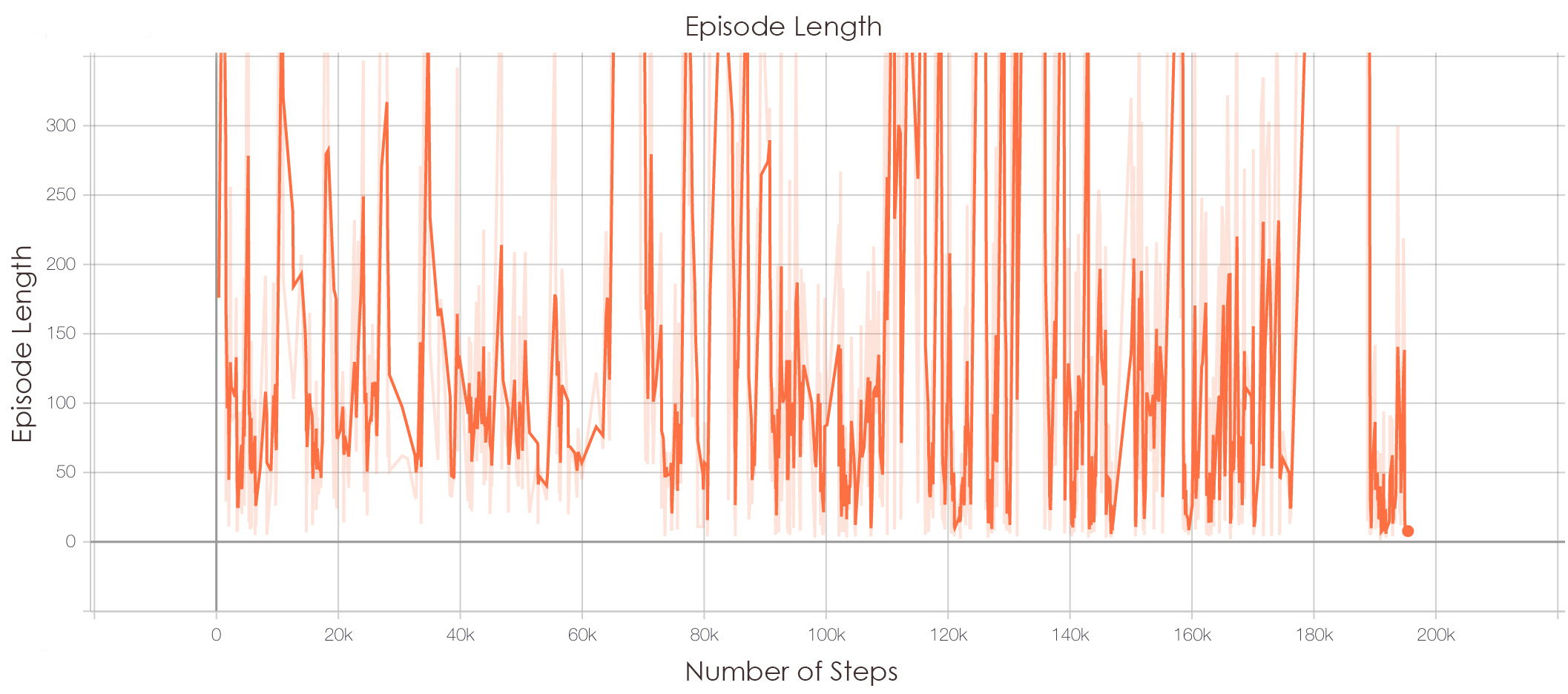

Graph 1 demonstrates our overall trend on the episode length. Specifically, it is measured through the number of steps, or, rather, actions taken by the agent. Overall, it took a total of 197,000 steps during training and the general trend of the episode length decreases throughout the graph. This trend is supported in our following graphs of the episode reward, epsilon, loss per steps (i.e., error rate), and the max Q-value. For comparison, 20,000 steps enabled the agent to solve 5x5 maps in a decent performance. With the increase of steps to a total of 197,000, our agent is now able to solve 7x7 mazes.

The graph spikes up and down in correspondence to the number of steps taken in the respective epsiode. Spiking up denotes that the episode length was longer, and therefore, the agent took more steps; contrary, spiking downwards means that the episode length was shorter, indicating that the agent took fewer steps to solve the maze. Generally, episode lengths spikes upward when the agent is learning a new map.

With our episode reward graph (i.e., Graph 2), we measure how much our agent is rewarded based on the actions it took and whether it reaches the goal or if the mission ends prematurely, i.e., running out of time or burning to death.

The following displays our reward system:

- Reaching a goal, in our case, touching an emerald block: +100

- Touching a fire: -50

- Touching Sea Lantern : -2

- Touching Beacon (outer walls): -2

- Touching Glass: -20

- Touching/Walking on carpet : +1

- Dying: -10

- Making a move: -1

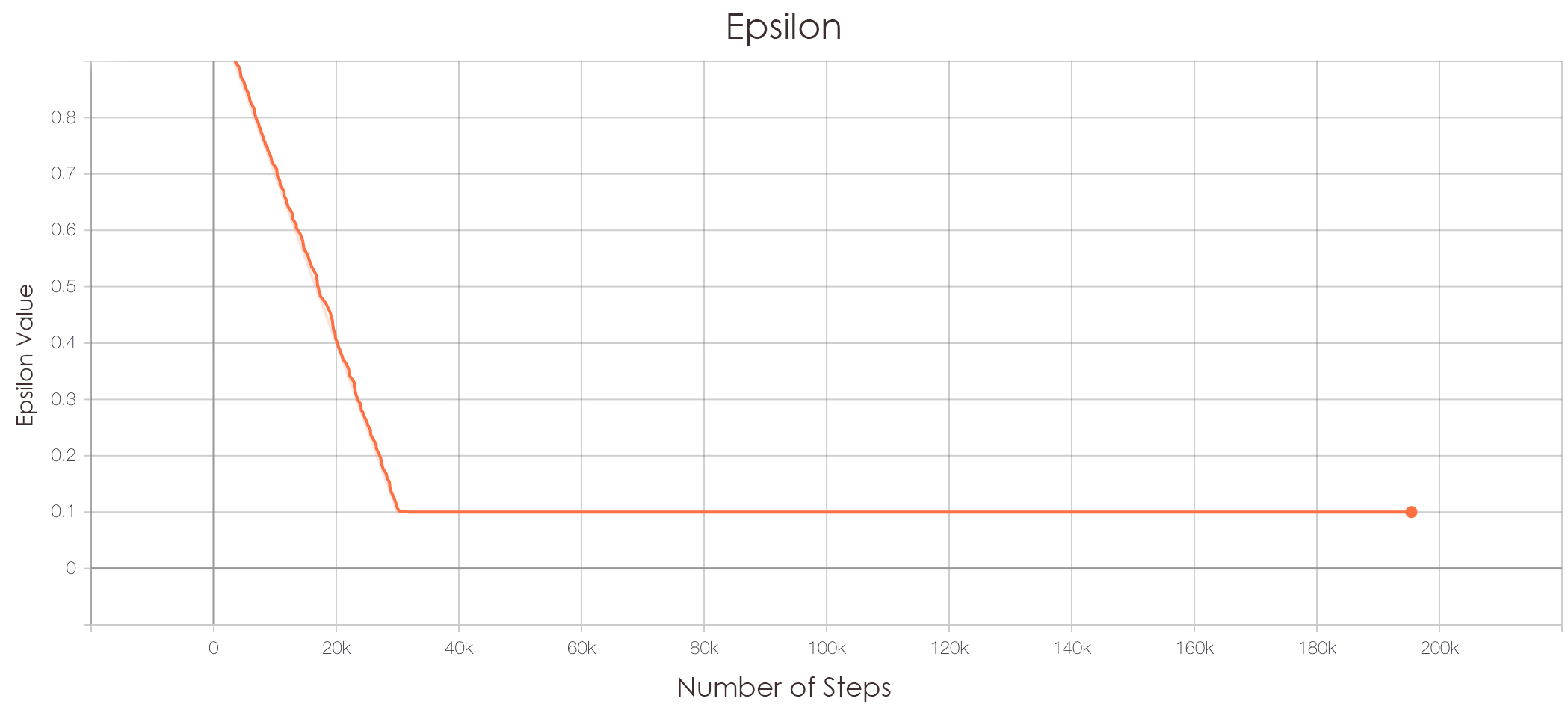

We want our agent to have its reward increasing to show that it is learning throughout its training sessions. Thus, the episode reward is relative to the number of steps the agent has taken. We estimate our graph to have numerous downward spikes due to our epsilon value - where our agent takes a random action as a way to explore the maze or its environment and avoid suboptimal convergence. However, throughout the entire graph, we can see that it gradually converges and stabilizes as epsilon decreases as seen in Graph 3.

The general trend with epsilon starts at 1, and in Deep-Q learning, we should aim for epsilon to decrease to 0.1 such that the agent no longer or seldom takes random actions. At 30,000 steps (as corresponding to our episode reward and episode length graph), our epsilon has decreased to 0.1. This means that our agent has stopped taking random actions, and therefore, is now making smarter moves. This greatly contributed to the success in the 7x7 maze.

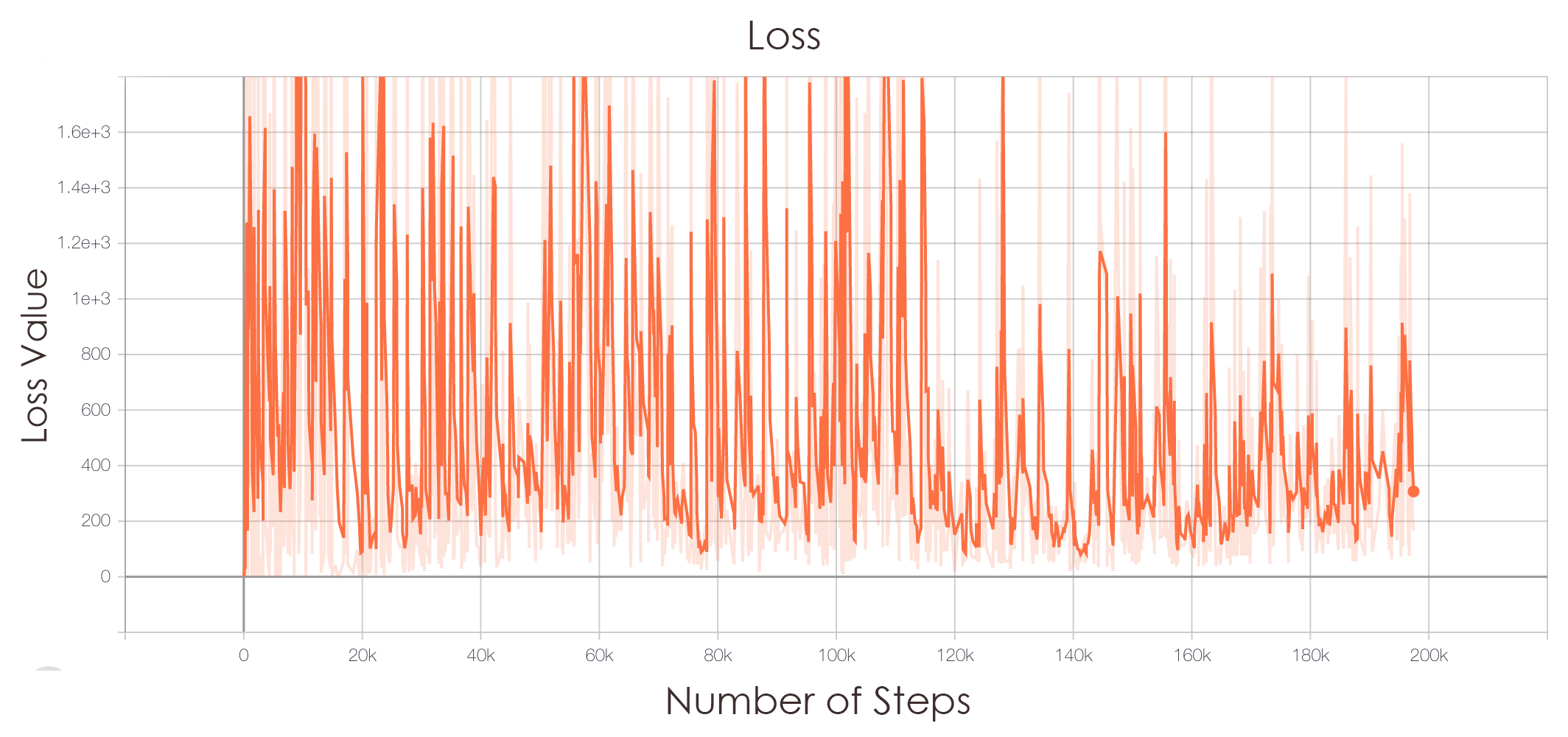

In machine learning, we aim to minimize our loss, or rather, the error rate as we train our agent. With Deep Q-learning, the agent should predict a move and its reward and select the action that will provide it with the highest reward. To ensure that our agent was minimizing its losses, we graphed the overall trend of our agent in respect to its error rate (Graph 4). We can see here that the error gradually decreases in respect to the number of steps our agent has taken. This finally leads us to our overall maximum Q-value trend.

We should aim to decrease the result of the loss function so that the agent performs better. Generally, the loss function greatly increases (ie spikes upwards) because the agent is learning a new map; when a new map is seen, the agent constantly dies in the fire or runs out of time to solve the maze. As the agent begins to learn the map, the loss function decreases as it is training.

Overall, our maximum Q-value increases which denotes a higher trend in performance in respect to the number of total steps taken. Our goal is to maximize the Q-value so that it helps the agent predict the next best action based on the expected reward. With a higher Q-value, it can choose the next best action and thereby minimizing loss.

We trained our agent for approximately 8 hours and 5 minutes. The hardware used to train our model were 2 * GTX 1080Ti (11GB GDDR5), Intel i7-6850K 3800Mhz (6 cores, 12 threads, 15MB Cache) 24GB RAM.

Previously, we struggled with controlling the fire because it is beyond our control in terms of its speed and direction(s) when the fire is not blocked by a sea lantern. As aforementioned, we combatted this by randomly placing glass blocks instead of netherrack below the carpet to aid the agent in the training in 7x7 maps as well as to add more random dynamics into the environment. By readjusting our approach in our randomized maze creation, we can conclude that we successfully trained our agent for 7x7 maps.

Looking Back

Originally, we had planned for our agent to be able to pick up resources as it learned to avoid fire and to find a map. We also wanted our agent to succeed in solving 10x10 mazes. However, after receiving feedback from our peers and our Professor, we decided to focus on making our agent ‘smarter’ in solving the mazes with a dynamic, random factor of the spreading fire - rather than overload our agent in doing multiple tasks (ie having our agent collect resources simultaneously). As a result, our project became an agent that can effectively solve 7x7 mazes in a reasonably fast time with minimal reward loss. Meanwhile, we redefined our 10x10 goal as a challenge for this project.

Video

Resources Used

[1], [2]. Matiisen, Tambet. “Guest Post (Part I): Demystifying Deep Reinforcement Learning.” Intel AI, Intel. Date Published on 22 December 2015. URL. https://www.intel.ai/demystifying-deep-reinforcement-learning/#gs.eggq2z

AccessNowhere. “【Electro】渚-Silent Electro Remix-【CLANNAD】.” Youtube.

Britz, Denny. Reinforcement Learning.(2019). GitHub Repository. https://github.com/dennybritz/reinforcement-learning/tree/master/DQN

Juliani, Arthur. “Simple Reinforcement Learning with Tensorflow Part 4: Deep Q-Networks and Beyond.” Medium, Medium, Date Published on 2 September 2016. URL. https://medium.com/@awjuliani/simple-reinforcement-learning-with-tensorflow-part-4-deep-q-networks-and-beyond-8438a3e2b8df

Tabular_learning.py tutorial, included in Malmo